Tackling Barriers and Solving Behavior Change

Ensuring that kids are getting the daily balanced and active play they need requires tackling behavioral barriers to play: structural and behavioral issues. Most of the work to date, however, has focused on addressing the former.

For example, KABOOM! and other organizations have worked hard to tackle barriers such as lack of access to playgrounds and reduced recess time in schools, with KABOOM! building thousands of playgrounds across America for kids in need and catalyzing the building, improving, and opening of thousands more.

Equally important, however, is solving barriers related to individual behavior change—how do we enable parents and caregivers to include more active play in their kids’ daily activities? In most communities, kids can’t get to playgrounds if adults don’t bring them there. In addition to safety concerns, there are certainly real constraints on time—parents work long hours, and kids have school, homework, and other activities. However, we believe there are also behavioral barriers that can be addressed through innovative solutions focused on the psychological obstacles of active play.

The Decision Making Process Around Play

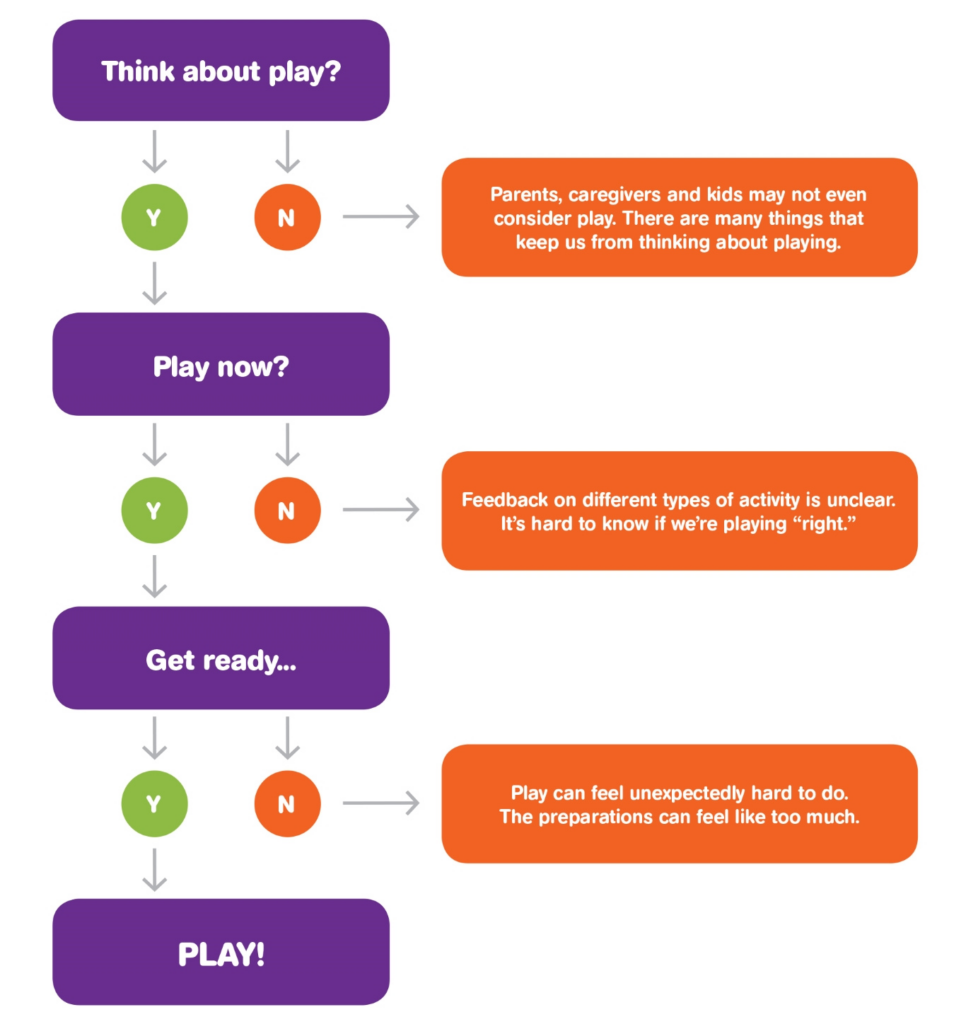

At its most basic, the process of “playing” appears simple. The parent or caregiver decides to take the child out to play, and then they do it, right? In actuality, the process is more complex. When we look at the full decision-making process, and the context in which it occurs, we might see that it looks something like this:

Lisa gets home from work around 4:10 p.m. The bus drops off her 6-year-old son Damien 20 minutes later. He complains that he’s hungry, so Lisa lets him snack while she cooks dinner and does chores. At some point—maybe earlier in the day, maybe while he’s snacking, maybe when the weather clears up— Lisa needs to consider the option of going to the playground and decide that it’s worth interrupting or forgoing other tasks to bring Damien out to play. Then Lisa gets ready. She packs a bag with snacks, extra clothes, books, and toys, dresses Damien in play clothes, and then, finally, they go out to play—out the door and down to the park.

Note the key actions in this story in bold: Lisa must consider play, then decide to take Damien out, and then prepare to play, before she can actually take him to play at the park. These actions are all potential behavioral “sticking points,” or what we like to call “bottlenecks,” starting with a step most of us are unaware of—just the consideration of the option to play. And again, as we can see by Lisa’s busy schedule and Damien’s hungry belly, this whole decision-making process doesn’t occur in a vacuum—there are numerous contextual features that may affect what actions are taken along the way. On the following page is a map of that decision-making process with the key behavioral bottlenecks called out in orange. Next, we discuss these three major bottlenecks and the psychological effects around them.

Behavioral Bottlenecks to Play

How parents and caregivers may not even consider play

From a behavioral perspective, Lisa’s consideration of the option of play—her “moment of choice”—is actually an important step. Kids today have many activities that occur at specific times—school, meals, TV shows, etc.—but play isn’t usually a planned event, and that means parents and caregivers (and kids) may not even think about play. Or, if they do, the timing is wrong—they’re passing a playground on the way to a doctor’s appointment, or coming home for dinner after a long day.

As individuals, we make many apparent “decisions” that are not really decisions at all—rather, we did not even consider making the choice, and so we ended up sliding into a default or routine action with little conscious thought. Or, we may indeed consider the choice—but at the wrong time, when there is nothing we can do to act on it. This is especially true when there is no clear moment of action, or when we are busy with many other things. For example, many people sign up for introductory trial periods and find themselves paying for magazines, product shipments, or other subscriptions long after they intended to end the contract. Without a specific moment to act, it is often easiest to just continue the status quo.

This is one of the reasons education and outreach campaigns are often not as effective as their organizers hope. Education works best when there is a careful choice being made, and the target individual has a specific moment to consciously reflect on the pros and cons of a decision. With active play, it’s easy for families to get caught up in all the other daily tasks and decisions and never have a moment to even consider the choice to play.

Feedback on Different Types of Activities is Unclear

It may be unclear to parents or caregivers whether their kids are sticking to the right “play diet.” Parents don’t see any measurement of how many hours in a week their child has been playing, whether indoors or outdoors. Organized activities and school work have more salient “units” of measurement—soccer practice happens three times a week, school goes from 8 a.m. to 3 p.m., homework gets finished. Further, the benefits of play are not immediate, so that is not a source of feedback either.

Timely, salient feedback is an important behavioral cue. When we can know the impact of our actions, and how we are doing relative to some standard or norm, we are much more likely to change our behavior. For example, Opower is a company that sends people letters telling them how their energy consumption compares with that of their efficient neighbors. Even given just this simple feedback, people reduce their energy consumption by 2-3%. Energy prices would have to go up by more than 20% to achieve the same change!

With active play, it’s hard to know if you’re “doing it right”. The impacts of behavior change show up years, if not decades, after the actions.